Digest #3: New Jersey Travelogue

Our studio traveled to New Jersey for a week to see first-hand how coastal communities, big and small, adapt to rising waters. Here are a few of our observations.

Welcome to Travel Week

During the third week of February the Small Town Adaptation and Resilience (STAR) Studio at the University of Pennsylvania traveled to southern New Jersey to visit different locations threatened by sea level rise. The aim was to get better acquainted with the reality on the ground in areas at risk of flooding and saltwater intrusion to better understand the environmental, social, and economic impacts. The members of the studio identified two primary locations of interest as examples of threatened urban areas: Salem County and Atlantic City.

A daily snapshot of our travel week in southern New Jersey. Source: Studio Team

Throughout the week, we were based at Bradley Beach - a small seaside town on the Northeastern shore of the New Jersey coastal plain. Our journey started with a visit to the Pine Barrens at Cattus Island County Park, where we got our first approximation of the local flora and fauna, the impact of salt water intrusion on local forests, and efforts to preserve New Jersey's ecology. The following day we visited the historical town of Salem, which has experienced severe shocks to the local economy in recent years that hinder investments in infrastructure and climate adaptation. We explored both the urban core and nearby points of interest like the port, the PSEG Salem Nuclear power plant, and Kates Creek Meadow Observation Point. Next, we met with representatives of SCAPE Landscape Architecture Studio, HR&A Advisors, and Rebuild By Design to learn more about various projects along the Atlantic coast, such as a living shoreline project site that we visited on Staten Island. Finally, we visited a range of locations in Atlantic City to better observe the contrast in adaptation investments and infrastructure in locations with a strong real estate market and economic drivers.

Click on the map to explore our destinations throughout New Jersey and New York City. Source: Google Maps

Why We Chose Salem and Atlantic City

We chose Salem as a small town on the riverine floodplain facing a variety of social, economic, and environmental challenges. In contrast, Atlantic City stands as a medium-sized town with significant and vulnerable economic assets along the barrier islands.

We first noticed Salem on the Council for Environmental Quality’s Climate and Economic Screening Tool (CEJST). CEJST was designed to help the federal government meet its tool of directing 40% of its infrastructure funding to historically disadvantaged communities facing environmental issues. According to CEJST and other data sources, Salem faces a plummeting population, no reliable economic engine, and extremely high flood risk, among a range of other economic and climate challenges.

Digging further, we found more reasons that made Salem a compelling case study. For example, until recently, the city was facing $11 million in debt, one of a myriad of reasons that led residents to vote to sell their water infrastructure to American Water New Jersey, a private company. Yet, we also found things that surprised us and added more nuance to the situation. For example, Salem was founded nearly a hundred years before the US itself and has a clear sense of identity marked by abundant historic infrastructure, a Nobel laureate, and a hilarious (but apocryphal) story of one prominent 19th century resident bravely eating a tomato.

In one sense, Atlantic City and Salem both exemplify the challenges that economically distressed towns in southern New Jersey face in adapting to climate change. Yet they also represent two poles of a paradigm: despite Atlantic City’s struggles, it possesses many things that Salem does not, such as widespread name recognition, public awareness of some of its challenges, and—crucially—local capacity state-level support and funding to enable it to build defensive infrastructure, draft adaptation plans, and more. Salem lacks these resources; it is actively privatizing some of its critical infrastructure, has a part-time mayor, and outsources its planning and engineering to a private firm. So, while Salem and Atlantic City face comparable climate challenges, they have strongly divergent options for how they will adapt, whether that be retreat, restructuring, or revitalization. We think of them therefore as compelling case studies in their own right while also serving as interesting points of comparison with each other in order to tease out the nuances of climate adaptation in southern New Jersey.

The following sections are organized around themes of Retreat, Revive and Restructure.

Retreat

The studio defines retreat as a process of displacement, a concept that is adaptable to different contexts. During our site visit, we observed the financial retreat of industries, residential retreat from at-risk areas, and ecological retreat of native plant communities due to saltwater intrusion.

The estuaries of the Southeast Jersey Back Bay and Delaware Bay create a diverse range of coastal environments. As a result, sea-level rise (SLR) cannot be viewed merely as a uniform change in elevation. The annual 1% high water level varies by as much as 8 feet from the Central Jersey coast to Cape May, indicating that the impact of storm surges can exhibit complex patterns due to the scattering of wave momentum by underwater and coastal sediments.

Sea-level rise can hasten coastal erosion, endangering infrastructure, homes, and ecosystems. This erosion may diminish natural barriers that safeguard coastal communities from the sea, increasing their vulnerability to storms and flooding. The sediment composition of South Jersey—a mix of mud flat fine grain sediments and coastal quartz sand accretion—highlights its nature as a passive continental margin. This means the coastline might be evolving independently at a rate faster than that caused by SLR-induced inundation. South Jersey has seen a loss of land and tidal marshes adjacent to meandering streams, and inlets have been widened by storms, complicating efforts to effectively close them. Conversely, coastal dunes that accumulate more sediments can expand and gain elevation through wind deposition, thereby offering greater protection to the most sought-after coastal vacation communities, while back bay waterfronts become increasingly vulnerable.

Subsidence, the gradual sinking of land, can result from natural processes like sediment compaction or human activities such as groundwater extraction. Coastal communities may face higher relative sea-level rise rates due to subsidence, a situation that worsens near backbay waterfronts.

Salem and Atlantic City illustrate these dynamics concurrently. The expansion of coastal dunes facilitates the Army Corps of Engineers' efforts to build coastal infrastructure protecting resort areas from storms. Meanwhile, areas with mud flats and backbays are at a disadvantage, beginning to subside and erode more rapidly.

Industrial Retreat in Salem

On Monday, February 19, 2024, our studio conducted a field walk in Salem County, NJ. As we traversed through the neighborhood via Broadway Street to the Port of Salem, a collective curiosity guided our fieldwork as to how the once-thriving harbor area deteriorated. In 1968, the South Jersey Port Corporation was created to operate marine shipping terminals in the South Jersey Port District which consists of 7 counties: Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, Salem, Cumberland, Mercer, and Cape May. As one of the oldest ports on the East Coast, the Port of Salem also has a critical identity in international trade.

The site mainly consists of large vacant industrial lots and a closed landfill. There is limited operation in material export and transportation, such as sand, gravel, dry bulk, motor vehicles, and fishing apparel. In 2018, Salem Waterfront Redevelopment Zone Plan was endorsed by the Salem Planning Board to revitalize the city economically. Shift in federal policy fuels in investment. In 2021, South Jersey Ports received a $9 million grant from the US Department of Transportation for expansion of the Port’s barge capacity and intermodal rail connectivity, following with the proposal of Salem Offshore Wind Terminal in 2022. Also, the Infrastructure for Rebuilding America (INFRA) grant supports the port’s existing sand and concrete shipments while strengthening New Jersey’s leadership in manufacturing key components for the offshore wind industry off the Atlantic Coast.

With an increasing investment to the Port, concerns over its climate challenges loom. It is noteworthy that a majority of the Port’s redevelopment area is located within the 6’ SLR extent and the 100-year flood zone. In consideration of the economic burden for infrastructural protection, it is questioned if it would be more beneficial to disinvest and retreat the critical industrial development from the current Port area? Or if we stay, should the future industry be adaptive to water, e.g. blue-green economy?

Collage of sites around the relatively vacant Port of Salem. Source: Lillian Chung

Salem’s Unplanned Residential Retreat

On paper, Salem is an obvious candidate for retreat: the population has been declining for decades, local jobs have dried up, and nearly the entire town is projected to flood regularly based on even the most conservative projections for the next 50 years. But on the ground, the lack of a plan for managing this process is leading to uneven, inequitable impacts: residents are leaving due to economic and climate pressure, leaving behind a patchwork of abandoned 19th century buildings and a city with more than 300 years of history. Given the likelihood that this attrition will continue, the residents of Salem deserve a coherent plan that will allow them to relocate confidently, on their own terms.

Market-driven Retreat in Pleasantville

Pleasantville, New Jersey, is a small city five miles west of Atlantic City. The town is surrounded by marshes bordering the Lakes and the Absecon Bays. Several residential developments occupy the historical low-lying marshlands, putting the neighborhood at risk of sea level rise and flooding. According to NJDEP, the Lakes Bay neighborhood is built on artificial fill with less than five feet in elevation. We visited Pleasantville’s Lake Bay area during our field visit to Atlantic City. The neighborhood is classified as a repetitive loss, according to an analysis prepared by Rutala Associates. Buildings classified as repetitive loss occur when they have a flood damage claim of over $1000 during a ten-year period.

Pleasantville Repetitive Loss Area Analysis by Rutula Associates

During our site visit, we noticed how the geopolitical landscape shapes the physical qualities of the neighborhood. The Lakes Bay area is experiencing a market-driven retreat, which occurs when families move away from vulnerable locations without government support. We witnessed scattered elevated structures towering over residences, juxtaposed against numerous abandoned lots reclaimed by pioneering species. The city lacks a holistic community-wide managed retreat that allows residents to move to safer areas. This uncoordinated retreat is also impacting the accessibility of state funding. After Superstorm Sandy, the city requested $1.4 million to buy out 22 properties. However, the application was contested by the NJDEP since the residences were not contiguous to one another. As we traversed the streets of the Lakes Bay neighborhood, the prevalence of properties and lands listed for sale underscored both the residents' willingness to retreat and their financial constraints to do so. This experience emphasized the need for coordinated intervention and resource allocation to facilitate a safe and equitable retreat process for all members of the community.

Gallery of photos from Pleasantville, NJ just outside of Atlantic City documenting the impacts of retreat. Source: STAR Studio

Isle de Jean Community Retreat

Prior to leaving for travel week, we were inspired by Liz Koslov’s The Case for Retreat, specifically thinking about her statement, “Retreat might reasonably be expected to follow from physical geography, to be based on factors such as elevation and proximity to the coast. Yet these cases show that it is based as much, if not more, on political and social geography” (379). With this framing of how retreat needs to be prioritized on community and their values, we have looked at the Isle de Jean Charles Resettlement Plan as a case study for a development plan that prioritized indigenous values and connections to land and community. Located in coastal Louisiana, Isle de Jean Charles is an island in Terrebonne Parish that is rapidly disappearing into the Gulf of Mexico due to coastal erosion and sea level rise. Once 22,000 acres, the island is now only 320 acres. Land where the predominantly indigenous population hunted, trapped, grazed animals, and farms in now open water. In 2016, Louisiana was awarded $48.3 million in Community Development Block Grant funds to work with residents of Isle de Jean Charles to develop and implement a structured and voluntary retreat from the island into safer communities. This includes developing The New Isle, a planned community about 40 miles north of Isle de Jean Charles that will include more than 500 homes, walking trails, a community center, commercial and retail space and other amenities designed in conjunction with island residents.

An assessment of Isle de Jean’s interventions. Source: Ruth Penberthy

Ghost Forests in the Pine Barrens

Parallel to the retreat of homes and industries, ecosystems have also been retreating in New Jersey due to flooding and saltwater intrusion. The Atlantic Coast was once covered by vast swathes of Atlantic White Cedar swamps, which were logged extensively by early colonists. The remaining Cedar forests were significantly affected by Superstorm Sandy and today approximately 20,000 acres of forest stand as compared to 135-140,000 acres prior to European settlement. During travel week, we visited Cattus Island County Park and walked through an Atlantic Cedar ghost forest – a term used to describe a forest that was once alive and vibrant. As a response to the devastating impacts of sea level rise on these forests and the multi-species ecosystems they support, the NJDEP is currently carrying out the largest Atlantic Cedar restoration project that has been proposed in the US. They aim to restore a minimum of 10,000 acres every 10 years at higher elevations, funded by a “Natural Resource Damages” pollution settlement as a result of fines from gas station leaks across the state. This attempt to restore “the kidneys of the Pine Barrens” will benefit wildlife restoration and public drinking water supplies and is an important program to understand how ecosystem restoration efforts are currently being funded and implemented.

Collage about Ghost Forests at Cattus Island near the Pine Barrens in New Jersey. Source: Johanny Bonilla

It was a cold windy afternoon and the sun shone obliquely through the trees. The last remains of recent snow edged the boardwalks as we weaved in and out of the trees. We pied an osprey nest, perched on a platform standing out among the dark ponds, a sign of hope in the sepia landscape. Dead trunks stood splintered, bare, poking in between the pines, thin outlines against the pale clouds. The ashen wood a sign of the salt encroaching underground.

We walked down the gravely trail, framed by yellow sea grass that swayed in the wind between the channels. We reached the narrow beach, hair whipping about our faces as we wondered at the houses on the water across the Silver Bay. The water lapping at the retreating sliver of land, grasses hanging on against the elements. The visit gave us an eerie sense of melancholy, of understanding just enough to feel unease, but not enough to grasp the true scale of what is going on at the Jersey Shore. - Delfina Vildosola

Atlantic City’s Changing Shoreline

The shoreline of Atlantic City has been shaped by both historical infill processes as well as retreat. The process of filling in marshy or low-lying areas to create new land and the parallel natural or human-induced movement of the shoreline inland over time has created a shifting edge that negotiates the arbitrary divide between land and water. Urban development, sea level rise, and environmental changes are just some of the processes that have contributed to this changing edge that we observed on our trip. Future climate resiliency plans for the city will have to consider this edge and how retreat, revitalisation, and restructuring can lead to new futures for the Atlantic City shoreline.

Click on the map to explore changing shorelines in ArcGIS Online. Source: Priyanjali Sinha and Nissim Lebovits

Revive

Rainproof NYC

Battery Park City Intertidal Structure Prototypes

The Battery Park City Authority (BPCA) in Battery Park City is advancing coastal protection projects to adapt to climate change. Design commenced in 2018, with initial pile restoration in 2020, and barrier system construction slated for 2022. The projects include the South Battery Park City Resiliency Project, creating a continuous flood barrier, and the Combined North & West Battery Park City Resiliency Project, addressing vulnerable areas with deployable barriers and new flood protection lines. These initiatives aim to reduce risks from storm surge and sea level rise for Battery Park City and neighboring areas. The BPCA Resiliency Projects, with a combined budget of $852M, emphasize interconnectedness and align with the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency Plan. The Battery Park City Intertidal Structure Prototypes exemplify a proactive approach to revitalization that prioritizes sustainability and long-term resilience. By integrating with the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency Plan and emphasizing interconnectedness, the project demonstrates a comprehensive strategy for revitalizing coastal communities in a way that ensures their viability and vitality in the face of climate change.

The Battery Park City Authority's (BPCA) emphasis on creating a continuous flood barrier demonstrates a proactive approach to infrastructure development that can be replicated in Salem and Atlantic City. By incorporating deployable barriers and flood protection measures, similar strategies can be implemented to safeguard critical infrastructure and residential areas in these communities, thereby enhancing their resilience to climate-related hazards. The funding mechanisms utilized for the Battery Park City Resiliency Projects, including public-private partnerships and dedicated budgets, offer valuable insights into financing strategies for revitalization initiatives. By leveraging various funding sources and engaging stakeholders effectively, Salem and Atlantic City can overcome financial barriers and mobilize resources for implementing resilience measures and revitalization projects. In conclusion, the Battery Park City Intertidal Structure Prototypes serve as a tangible example of effective climate change resilience measures that can inform and inspire revitalization efforts in Salem and Atlantic City. By drawing upon the specific methodologies, funding mechanisms, and interdisciplinary approaches employed in the Battery Park City projects, tailored strategies can be developed to promote sustainable development and resilience in these coastal areas.

Source: NYC

Scape Presentation & Living Breakwaters Excursion. Source: Mira Hart

“A Story of Floods” An AR Mural

Along the bayside facade of the Chelsea Boys and Girls Club in Atlantic City, bright blue and yellow paint depicts a watery scene of wave crests and fish. The public artwork, completed in 2022, isn't just for looks; a QR code, also displayed on the wall, allows visitors to enter an “augmented reality” where they can learn about sunny-day flooding and the City’s flood-prevention structures. As part of a multimedia project called “A Story of Floods” funded through the NJ Coastal Resiliency Art Program, the mural works to bring forth memories of flooding events and spark resiliency conversations among residents.

Climate change and disaster researchers have used the term “amnesia” to describe the cognitive bias where-in people forget about disasters as time passes. This can be part of the reason why a significant amount of climate action and preparedness efforts tend to occur only immediately after destructive events, while the memory of disaster is still fresh in people’s minds. The “A Story of Floods” mural seems to challenge this dynamic by activating or “reviving” these memories on a more regular basis. If effective, this could potentially lead to more climate preparedness and resilience work within the Atlantic City community. Like the many other projects we categorized under “revitalize” during our site visits and research, the mural amplifies something that already exists–collective memories of floods–to build a more resilient community.

An AR mural called “A Story of Floods” at the Chelsea Boys and Girls Club in Atlantic City. Source: STAR Studio

Restructure

The Demand for Restructure: People who don’t want to retreat and people who cannot retreat

There are different types of elevated housing in Atlantic City. South of Absecon Lighthouse, 0.3 miles away from the shoreline, workers are working on the new development of elevated housing.

Driving along the shore of Atlantic City is a learning process using different house elevation tools. Some people decided to leave room for storms and floods to reduce the impact they would receive, and some decided to build concrete and brick foundations, which would help prevent the houses from being washed away by the flood. This elevated housing standing alone in the retreat community of Pleasantville is another example. In these cases, there’s a concept of home beyond the concept of house. People who decide to elevate their homes are very possibly the people who will not retreat. This resistance to retreat would happen if it were not already anywhere in case of an action of retreat. Salem is different, but a significant portion of the population can’t retreat. Among this community of staying, there’s a demand for restructuring.

Different types of elevated housing in Atlantic City and people’s resolution to coping with rising tides.

Atlantic City elevated streets: Chelsea Heights neighborhood restructuring

After Hurricane Sandy, Atlantic City’s Back Bay Neighborhood of Chelsea Heights was completely underwater. Located on a former salt marsh and on some of the lowest lying land within the barrier island, the community is vulnerable to not just storm surges, but also flooding during full moon tides and routine rain events. In the past decade, the neighborhood has become a focal point for some unusual proposals aiming to restructure the community and protect from coastal threats spearheaded by researchers at Princeton University. The designs, created between 2013 and 2019 as part of the Structures of Coastal Resilience project, included elevating homes and roads as well as integrating new canals through the neighborhood, creating what the researchers are calling an “amphibious suburb.”.

Although the proposals are purely conceptual and lack implementation funds, they seem to have captured the imagination of some Atlantic City officials and impacted conversations and attitudes around resilience within the City. Elizabeth Terenick, Atlantic City’s Planning Director at the time, was quoted in a 2017 Guardian article praising the designs as an “exciting project.”

Built atop a former salt marsh, the Chelsea Heights neighborhood of Atlantic City is one of the lowest lying areas on the barrier island and is vulnerable to storm surge, high tides, and rainy-day flooding.

Researchers with the Structures of Coastal Resilience Project developed proposals to turn Chelsea Heights into a “Amphibious Suburb” through elevating streets and homes and creating canals.

Infrastructure Restructure: Rainproof NYC, transform the concrete into a sponge and live with the water

The Rainproof NYC document outlines key recommendations for restructuring infrastructures citywide to address the unpredictable future of increased extreme rainstorm events, storm surges, and sea level rise. It suggests three major approaches to consider for infrastructure improvement and restructuring:

Enhancing Detention and Capture Capabilities: New and rebuilt infrastructures should be designed to detain and capture rainwater or stormwater. This method aims to expand the city's capacity to handle more rain events and reduce risks, moving beyond reliance solely on Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) systems. Implementing systems for the capture and reuse of rainwater or stormwater within the water cycle across different infrastructures is crucial. This would enable the cycling and reuse of water during both wet and dry days, thus integrating it into the urban water management strategy.

Incorporating Scalable Measures: Infrastructure should include scalable measures like water squares and absorbent parks. These structures enhance citywide resilience by providing additional water storage capacity. They are designed to accommodate flooding during unpredictable rain or storm events, thereby offering a pragmatic solution to managing excess water in urban areas effectively.

Retrofitting Existing Infrastructure: There is a need to retrofit existing infrastructure to serve water detention or conveyance purposes. This involves adapting streets to remain functional and accessible during floods and transforming large open spaces, such as parking lots and university campuses, into supplemental areas for neighborhood water overflow. These modifications would allow for better water management during extreme weather events, ensuring that cities remain resilient and adaptive to changing climatic conditions.

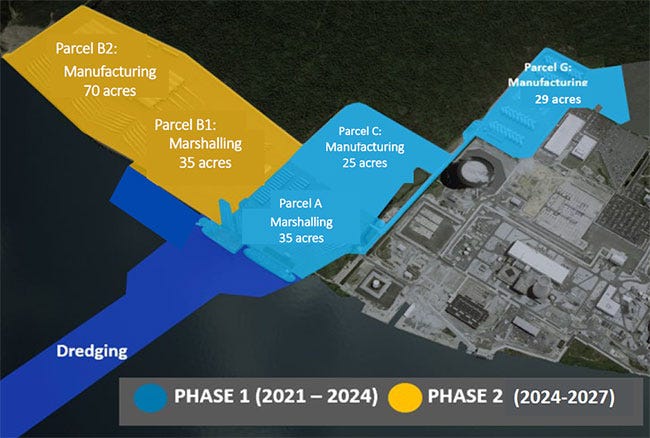

Economic Restructure: Salem County Offshore Wind Port

The wind port which is located in Lower Alloways Creek, adjacent to Salem City was sited there based on considerations of “minimizing environmental and residential impacts”. The long-term outlook for the Salem Offshore Wind Port suggests the creation of up to 1,500 “green” jobs across various sectors such as manufacturing, operations, and related services. The Marshalling Port, estimated to cost between $300-400 million, is proposed to open in late 2024, which began in late 2021, and said to generate hundreds of additional union jobs. In addition to job creation, the wind port is projected to stimulate up to $500 million in new economic activity annually within the state and the region. However, the economic resilience of Salem County and South Jersey hinges on not just the creation of jobs but also the ability to diversify the economic impact beyond the immediate scope of the wind port. This perspective prompts consideration of broader strategies for sustainable economic development and the need for a diversified and resilient "green" job market to ensure the long-term success of such ambitious projects. While the wind port is heralded as a significant contributor to the State's clean energy goals, questions arise about the economic resilience of the project, particularly in light of the withdrawal of Orsted as a potential tenant. The withdrawal of Orsted, with its projected creation of 200 jobs at the site and 15,000 jobs over a 25-year span, raises concerns about the project's adaptability to market dynamics and the need for diversification of "green" jobs.

New Jersey Wind Port Development Plan. Source: NJ.gov

Salem Excursion Stopmotion. Source: Mira Hart

The Diverse Defenses: Seawalls of Atlantic City and Beyond

In Atlantic City and nearby shores, the seawalls tell a special story about how we live with the sea. These walls, standing against the tides, show the mix of human-made and natural worlds. On our visit on February 22, 2024, we saw how the walls at Atlantic City Beach, Brigantine Beach, and Sunset Avenue each talk to the ocean in their own way.

Atlantic City Beach Seawall: In Atlantic City, the seawall is a robust and imposing structure. Here, the wall is more than a barrier; it is a symbol of strength and resilience, a man-made bastion where the bustling boardwalk, towering casinos, and urban vibrancy meet the force of the Atlantic. Yet, this stark concrete barrier also speaks to the tension between human endeavor and nature, a grey line dividing the constructed from the unconstructed.

Views: Where the seawall ends(left), Under the boardwalk looking at the wall (right)

Brigantine Beach Seawall: Journeying north to Brigantine Beach, the seawall transforms. It's a more humble structure here, incorporating a seating area on its crest. This wall marks the transition from the built environment to the natural world, nestled between the North Brigantine Natural Area and protective sand dunes to the south.

Views: On the Brigantine Beach Seawall(left), Looking at the seawall from the beach(right)

Sunset Avenue Seawall: The seawall at Sunset Avenue presents a contrasting narrative. Composed of weathered wood, marked by time and neglect, it stands not as a declaration but as a quiet testament to a more rugged, less polished aspect of coastal life. Here, the wall, eroded and graffitied, merges into the landscape, a part of the local fabric rather than an imposition upon it.

Bench at Sunset Avenue Seawall

Atlantic City Excursion Stopmotion. Source: Mira Hart

The evolvement of Rebuild By Design this organization

Rebuild by Design was not originally a standalone government organization but rather an initiative launched by the HUD in collaboration with the Rockefeller Foundation after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, aiming for resilient solutions in devastated areas. Post-competition, it became an independent body focused on global resilience and sustainable design, while maintaining governmental and private sector partnerships.

Comparatively, HafenCity GmbH, a city-owned company managing HafenCity's development in response to sea-level rise, shares similarities with RBD in government ties and community engagement, despite their structural differences. During our meeting with RBD, we know that in the U.S., public skepticism towards the government underscores the need for intermediaries like RBD to safeguard community interests. While directly replicating the German model may not be feasible, innovative strategies to maintain close government collaboration could enhance advocacy and implementation in the U.S. context.

Conclusion

During this travelogue and case study work, STAR studio group employed the "3 Rs"—Retreat, Revive, and Restructure—to first identify the strategies of climate adaptation in Coastal New Jersey and then study and analyze the challenges and possibilities in these places.

What are the major difficulties for communities to retreat? What is left after the retreat? How do we mitigate the impact of the projects? What can be an alternative to the revitalization of the area? Understanding that current climate adaptation is highly market-driven, do these places adapt? What are the cultural identities in these places, and what’s the meaning of community in climate adaptation? What are the roles of institutions and the state? What is the actual cost of a climate adaptation plan? Agriculture? Ecosystem? Will regenerative landscape be a good future for revitalization? What can we learn from other initiatives?

As a group, it’s an ongoing process for us to keep unfolding the details under the concept of "3 Rs". During this process, we will specify strategies and gradually build up our future toolkit for Small Town Adaptation and Resilience.